My Chaeronea: A Little Greek Museum’s New Exhibit About a Big Battle Gets Slightly Personal

An astonishing show at Athens highlights an epic clash that put a teenage Alexander the Great on the world map and inspires admiration for those who don’t give up the good fight.

ATHENS — Among the seminal battles that changed the course of history, few figure as prominently as the Battle of Chaeronea. The epic clash pitted the Macedonians led by King Philip II against an alliance of Greek city-states with Thebes and Athens at the vanguard. On a single summer’s day in a verdant Greek gorge, the Athenians wobbled, the Sacred Band of Thebes collapsed, and the civilizational balance of the planet shifted.

Such is the conceit of a stunning new exhibition at the Museum of Cycladic Art at Athens, “Chaeronea, 2 August 338 BC: A day that changed the world,” and it is a convincing one. The exhibit throws the spotlight on what was in effect the last of the truly ancient Greek battles.

That is because Philip II’s triumph established the Macedonians as the dominant power in Greece and the eastern Mediterranean during the remainder of his reign, and also propelled his son, an 18-year-old who would come to be known as Alexander the Great, to center stage. Amid the blood and broken bones — lots of broken bones — classical Greece receded forever, yielding to the more expansive Hellenistic world.

What if it had not? The question is too big to ponder, especially on such a polluted winter’s day as the Friday this correspondent went to visit the show, first entering the museum through the wrong entrance before realizing the exhibit is mainly in the museum’s Stathatos Mansion, a fanciful neoclassical villa built in 1895 by architect Ernst Ziller.

Chaeronea is better known for its role as a catalyst than for the combat that occurred there, which had little of the swash and buckle of, say, Salamis or Lepanto. Yet Alexander, at the head of the cavalry, did help his father’s army break the allied Greek line. After that the elite fighters of the Sacred Band of Thebes would be consigned to the history books, and more than a thousand Athenian hoplites were goners too.

Now, gleaming with ancient ferociousness behind a glass case, bronze arrowheads and lead sling shots can be seen with the inscriptions “of King Philip.” Inside another there is a Macedonian spear still sheathed with gold filigree. Intact bronze helmets, a coat of armor, and a pair of meticulously decorated ancient shields impart a sense of the noble to the whole, essentially brutish, affair.

The showdown started out innocently enough: The year prior, a Greek tribe called the Locrians, having encroached on the land surrounding the Oracle of Delphi, made Philip their commander. That was good news for the Macedonian monarch who had for years aspired to unite the city-states of southern Greece under his rule. A subsequent passage through Thermopylae and the conquest of Elateia were enough to sow panic at Athens. So, at the urging of the Athenian politician and persuasive orator Demosthenes, the Thebans and Athenians united in arms.

How violently they fell — and many Macedonians, too. Through the end of March a somewhat eerie display of the burial practices of the two opposing armies are on view: remnants from the Polyandrion, or mass grave, of the 254 Theban members of the sacred band, as well as the tumulus of the Macedonians.

After the battle, and with the apparent acquiescence of Philip, the Thebans fashioned a large rectangular pit into which they placed the fallen warriors and their grave goods in a formation that mimicked their battle flanks. When the Greek archaeologist Panagiotis Stamatakis uncovered the site in 1879, the skeletons he saw bore wounds from spears and swords, mangled limbs, and smashed up faces. Because they were defeated, though, they were buried without their weapons.

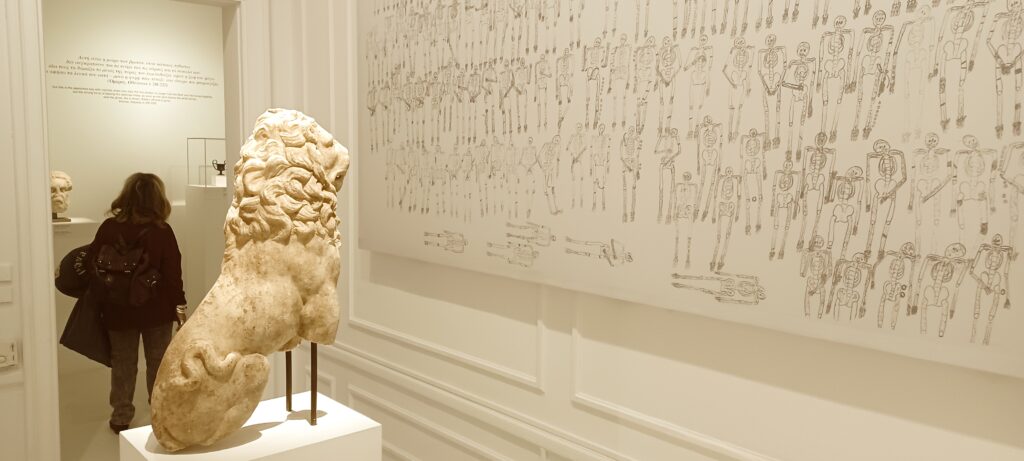

One of those skeletons and a few partially crushed skulls are on display here in the center of a high-ceilinged room with walls painted crisp white. Behind them is a replica, in miniature, of the Lion of Chaeronea. The original lion stood nearly 20 feet tall and can still be seen near the modern village of Chaeronea. The regal feline fixes a stoic gaze at a diagram depicting how the dead were found, in seven carefully arranged rows.

The Macedonians who fell in battle were cremated, as ordained by their king. In this way, according to the ancestral customs of the dynasty, they were honored as heroes. King Philip II wanted the funeral pyre itself to dominate the landscape, and at 22 feet high and 230 feet wide, it did.

What museum-goers see today are the bones and ossified ashes of the approximately 500 soldiers who were burned, now arranged under a circular glass showcase. Also on display are some of the sword handles, spear tips, epaulets, knives — and even a wreath — retrieved from the excavation site.

Stenciled in Greek and English on an otherwise spare wall in a short corridor that links the remains of the victorious and the defeated are these words of Homer: “But this is the appointed way with mortals, when one dies. For the sinews no longer hold the flesh and the bones together, but the strong force of blazing fire destroys these, as soon as the spirit leaves the white bones, and the ghost, like a dream, flutters off and is gone.”

Really? Those brave phantoms, whether of Greek or other extraction — and at the moment, I am thinking of my own unmet chaverim fighting tough battles just east of here — are the spirits that convert imperfect history into the future.

A remarkable exhibit like this might not break the internet, but in less cluttered times it would make more waves. Certainly it makes this correspondent proud to be a part, however fleetingly in this fractured post-Chaeronic sweep of time, of the city that, judging by the Manhattanish whoosh of traffic outside, did in the end win.