Carnegie Hall Goes Weimar

The music mecca turns to 1920s Berlin for inspiration.

At the center of Carnegie Hall’s announcement of its 2023-24 season is “Fall of the Weimar Republic: Dancing on the Precipice,” a festival stretched over five months devoted to the beautiful and broken years before the German cataclysm. For music impresarios as well as intellectuals, it appears as if Weimar lives again.

The season will open on October 4, with a slate that anticipates a return to pre-pandemic levels of attendance. According to the Associated Press, Carnegie has averaged 89 percent capacity this season, down from 93 percent in 2018-19. Its director, Sir Clive Gillinson, observed that after Covid, “people were desperate to get back to live entertainment, not just music.”

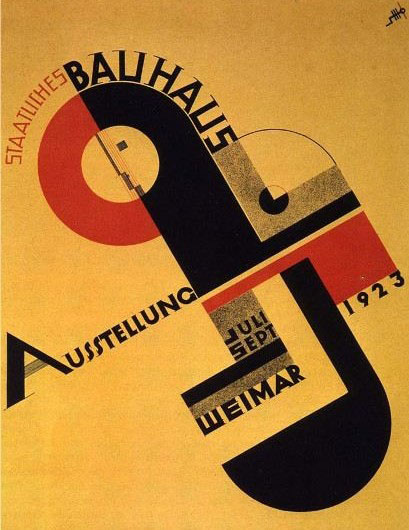

As part of “Fall,” the New York institution plans 27 concerts as well as an “Underground” series that encompasses cabaret and jazz in an effort to open up a cultural wormhole between Berlin in, say, 1923, and Manhattan in 2023. Mr. Gillinson told the Sun that such a theme has been a long held dream, and in the works for three years.

The Weimar Republic lasted from 1918, with the end of the First World War, to 1933, when Adolf Hitler acceded to the chancellorship. It was beset by hyperinflation, rollicking political instability, politically motivated murders, and an efflorescence of artistic flourishing. The first concentration camp, Dachau, opened the same year it ended.

At a press conference, Mr. Gillinson explained that “Weimer demonstrates many lessons about the fragility of democracy that are as relevant today as they were then and it makes it so clear that democracy is a very fragile flower that has to be nurtured and protected all the time.”

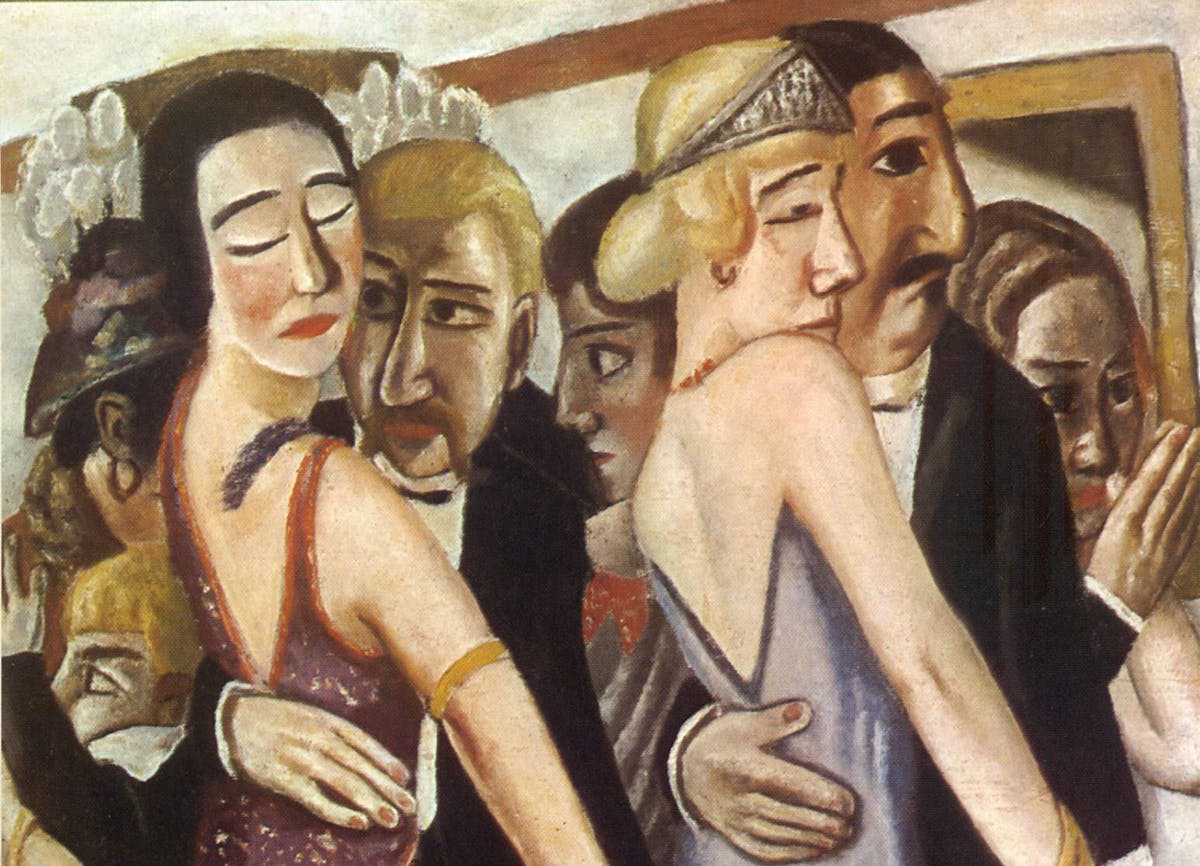

Mr. Gillinson called Weimar one of the “most consequential and complex chapters in human history,” and a video trailer for the festival marked its “pulsating possibilities” by alternating gyrating dancers, crooning singers, and goose-stepping fascists.

Carnegie Hall’s 170 performances planned for 2023-24 will include such Weimar excursions as “Sequins and Satire, Divas and Disruptors: The Wild Women of the Weimar Republic” and “the Golden Twenties,” as well as a collaboration between the actor Alan Cumming and the Hot Sardines, who intend to evoke “1920s Berlin, where cabarets thrummed with American jazz.”

Others have found the prospect of comparing the Trump years — culminating with the events of January 6 — to the buildup to the Third Reich too resonant to ignore. The Substacker Andrew Sullivan wrote in 2020 that the “Weimarization of American politics may be picking up steam” and postulated a “Weimar dynamic” of “accelerating illegitimacy.”

In 2015, Roger Cohen penned a column for the New York Times titled “Trump’s Weimar America,” which he described as “an angry nation stung by two lost wars, its politics veering to the extremes, its mood vengeful.” That same year, Rod Dreher allowed that he “used the term ‘Weimar America’ to describe our country today.”

The historian Niall Ferguson — who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Weimar — notes in the Washington Post that this turn to what he calls “Weimerica” is not new; “within a few years of its collapse in 1933, Americans had adopted Weimar as their very own nightmare scenario” for what can happen to a “diseased democracy.”

Yet for Mr. Ferguson, “no amount of repetition will erase the enormous differences between the U.S. today and Germany 90 years ago.” Whatever maladies America faces, he adds, they have “almost nothing in common with interwar German fascism, which was about racial persecution and ultimately annihilation, economic autarky and actual war.”

Convergences and divergences aside, the “Fall of the Weimar Republic” festival begins January 20, 2024, with a concert from the Cleveland Orchestra and conductor Franz Welser-Möst, playing Krenek, the Adagio from Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, and two works by Béla Bartók.